Telegram: I am Sergey Kuznetsov

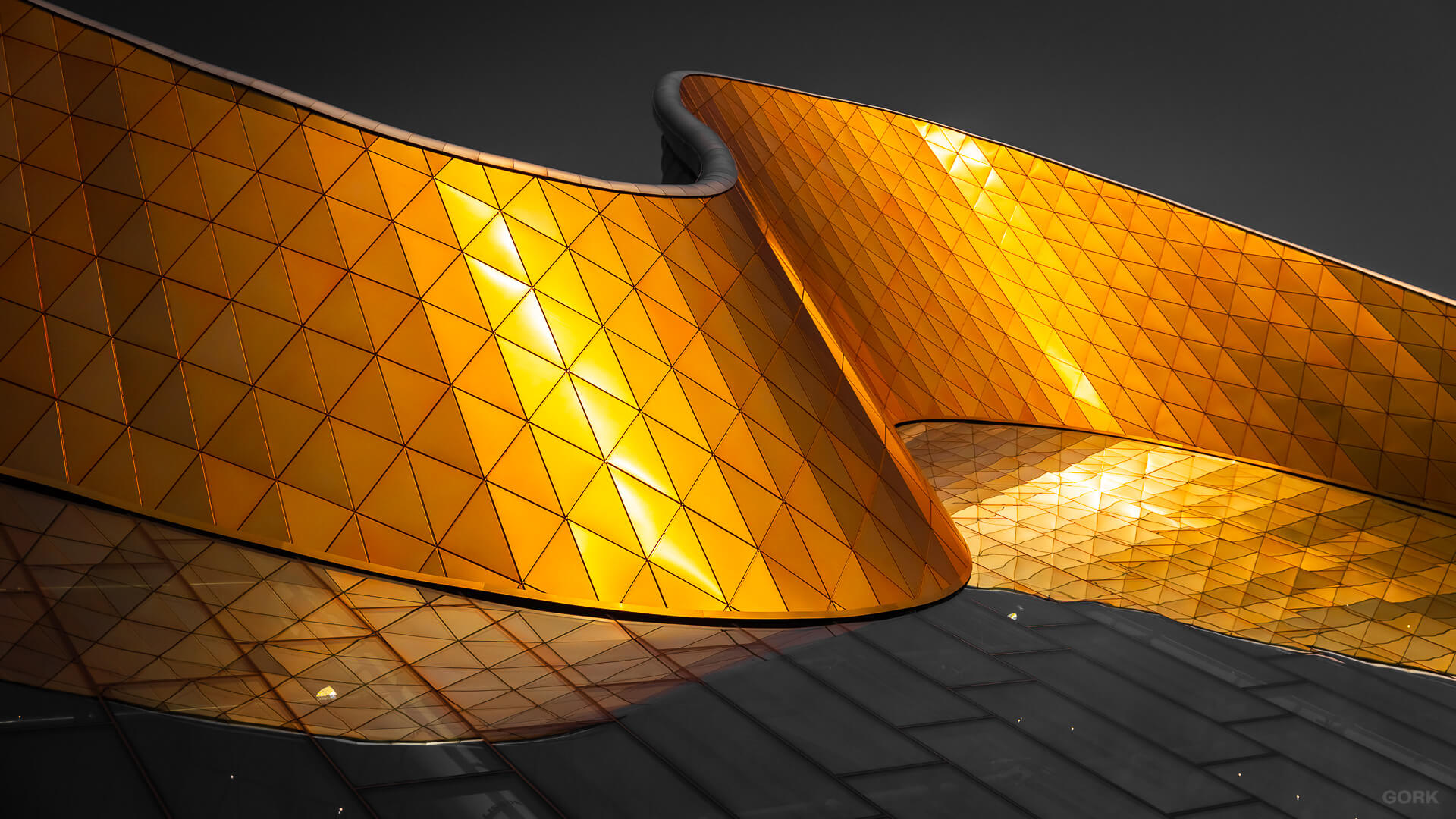

Photo: Gork Journal

Although I am not a third-generation native Muscovite, I witnessed the transformations that began in the post-Luzhkov era: the prevalence of banners around the Garden Ring, chaotic parking, the lack of an urbanized environment, and gaudy, if not tasteless, architecture. Since then, the approach to shaping the capital’s image has changed, Moscow of the nineties and zeros and modern Moscow are two different cities. The Chief Architect of Moscow, Sergey Kuznetsov (SK), helps us delve deeper into this topic:

GJ — Sergey, can you describe the state of Moscow’s architectural fund when you took office as the chief architect?

SK — I immediately focused on working with new projects and transforming the professional community. The success of quality architecture is about a professional, competitive, developed environment with a wide range of competencies, from architects and engineers to sociologists and philosophers. In 2012, this was practically non-existent. The lion’s share of projects was done by state institutes, where your boss was also your client. Such an approach bred architecture of dubious essence and indisputable quality. All key sites were developed in this way. Even private objects went through such a form of bureaucracy for approval. Therefore, the key subject of assessment and analysis became the complete modernization of the professional community’s work and new sites with fundamentally different architectural quality. I believe the progress on these fronts has been substantial. Since 2012, the architectural market in Moscow has grown tenfold, and now the capital employs over a hundred highly qualified architectural bureaus.

GJ — It's hard to imagine that the approach used to be just like that. I recently became acquainted with a book by Andrey Bokov about architectural visionaries of the late last century, which describes the scant competitive environment and private practice during the USSR era.

Photo: Gork Journal

Although I am not a third-generation native Muscovite, I witnessed the transformations that began in the post-Luzhkov era: the prevalence of banners around the Garden Ring, chaotic parking, the lack of an urbanized environment, and gaudy, if not tasteless, architecture. Since then, the approach to shaping the capital’s image has changed, Moscow of the nineties and zeros and modern Moscow are two different cities. The Chief Architect of Moscow, Sergey Kuznetsov (SK), helps us delve deeper into this topic:

GJ — Sergey, can you describe the state of Moscow’s architectural fund when you took office as the chief architect?

SK — I immediately focused on working with new projects and transforming the professional community. The success of quality architecture is about a professional, competitive, developed environment with a wide range of competencies, from architects and engineers to sociologists and philosophers. In 2012, this was practically non-existent. The lion’s share of projects was done by state institutes, where your boss was also your client. Such an approach bred architecture of dubious essence and indisputable quality. All key sites were developed in this way. Even private objects went through such a form of bureaucracy for approval. Therefore, the key subject of assessment and analysis became the complete modernization of the professional community’s work and new sites with fundamentally different architectural quality. I believe the progress on these fronts has been substantial. Since 2012, the architectural market in Moscow has grown tenfold, and now the capital employs over a hundred highly qualified architectural bureaus.

GJ — It's hard to imagine that the approach used to be just like that. I recently became acquainted with a book by Andrey Bokov about architectural visionaries of the late last century, which describes the scant competitive environment and private practice during the USSR era.

SK — I am not familiar with Andrey Bokov’s book. I can say that in the direction of private practice and architectural competitions in the Soviet Union, there were different periods. From the prosperity and quite famous competitions of the 20s-30s of the 20th century, to a long period of stagnation that lasted right up to the era of early Russia. The problem I observed, both as an architect and later, from the position of the chief architect, was that the majority of architectural projects were concentrated in the hands of state institutes. Such a model negated competition and the very idea of architectural competitions, and did not allow for the development of private practice. Responsible architectural figures saw this problem and had the authority and competencies to change it, but did not change the approach, as it went against their own interests. As a result, this critically affected the quality of Moscow’s architecture of that period.

GJ — Is it possible to export Moscow’s architectural experience to the regions of Russia? Examples like my native Nizhny Novgorod are more likely an exception, and the situation in many regions remains quite sad.

SK — It can be exported, but is there a demand? Everything that happens in Moscow is the merit of one person — Sergey Semyonovich Sobyanin. It all rests on his enthusiasm, energy, and passion to constantly make things better. He invited me to work, and any of my initiatives without his support would mean nothing. We need to appoint people like Sergey Semyonovich. Nizhny started to develop with the arrival of Gleb Nikitin — this is a regional head who is interested in development. A similar situation is in Kazan, and we actively communicate with such people, meet, and help. There is no secret, not only Moscow’s but also global experience is available, you just have to take it. The question is only whether you want it or not.

GJ — Is it possible to export Moscow’s architectural experience to the regions of Russia? Examples like my native Nizhny Novgorod are more likely an exception, and the situation in many regions remains quite sad.

SK — It can be exported, but is there a demand? Everything that happens in Moscow is the merit of one person — Sergey Semyonovich Sobyanin. It all rests on his enthusiasm, energy, and passion to constantly make things better. He invited me to work, and any of my initiatives without his support would mean nothing. We need to appoint people like Sergey Semyonovich. Nizhny started to develop with the arrival of Gleb Nikitin — this is a regional head who is interested in development. A similar situation is in Kazan, and we actively communicate with such people, meet, and help. There is no secret, not only Moscow’s but also global experience is available, you just have to take it. The question is only whether you want it or not.

When you come to Krasnodar, where we made the stadium and our colleagues a park, the situation is different: an oasis and trash around. You realize that for the local authorities, urban environment and architecture are not a priority. It’s simply useless to broadcast experience, standards there, where the immediate environment of the city’s main architectural masterpiece is being built up with identical residential houses. I don’t know who personally deals with this, but this should not be done under any circumstances. Galitsky needs the development of the urban environment, but they don’t. For Krasnodar, Galitsky is like the hen that laid the golden egg, and instead of investing this egg profitably and earning income, they just try to actively break it. In Moscow, for example, when businessmen and major patrons want to participate in a project, they are given the green light and support. Mikhelson wanted to make HPP-2 and put his sculpture, which for me is a complete delight — he received city support and all the necessary permissions. The more active and interested people there are, the better our country will be. It’s obvious.

GJ — What criteria must a project have to get the "green light" for construction, and is there a checklist you consider when approving projects?

SK — We intentionally do not standardize this document, because, on one hand, it filters out non-viable projects, but on the other hand, it stops development. A project can be executed according to standards, but we understand that it could have been done even better. With the development of the professional developer community, the economy, and technological capabilities, the bar of requirements is constantly raised, leading to a natural evolution process. The checklist today and its version from five years ago are completely different. Here are just a few points worth noting:

And finally, one more key thing. It is important for clients, who engage an architect to work on a project, to keep in mind that from this moment we are working with the architect, and you cannot cut him off at every turn and threaten with dismissal. The choice of a specialist should be conscious, and you should interact with him respecting his decisions. You can change an architect, but with a high probability, the situation will repeat. One must take the authorial vision into account — it’s a culture of work, a culture of creating real estate objects.

@gorkjournal

SK — We intentionally do not standardize this document, because, on one hand, it filters out non-viable projects, but on the other hand, it stops development. A project can be executed according to standards, but we understand that it could have been done even better. With the development of the professional developer community, the economy, and technological capabilities, the bar of requirements is constantly raised, leading to a natural evolution process. The checklist today and its version from five years ago are completely different. Here are just a few points worth noting:

- Non-typical development (Resolution 305)

- Plastic and diverse geometry of architectural form

- Engaging architects with interesting and authorial vision

- Presence of recognizable iconic buildings in the project

- Use of high-quality and modern materials

- Designing public spaces according to the principle of the facade-project (bright, individual with some findings)

- Night lighting (one should not underestimate the appearance of a building in which the viewer sees it half of the day)

- Silhouette of development

- Continuous filling of the street line

- Functional diversity, including the mandatory presence of public spaces on the ground floors with continuous glazing, presence of large doors, and a transparent entrance group.

And finally, one more key thing. It is important for clients, who engage an architect to work on a project, to keep in mind that from this moment we are working with the architect, and you cannot cut him off at every turn and threaten with dismissal. The choice of a specialist should be conscious, and you should interact with him respecting his decisions. You can change an architect, but with a high probability, the situation will repeat. One must take the authorial vision into account — it’s a culture of work, a culture of creating real estate objects.

@gorkjournal